|

In Chapter 25,

From Kurgans to Pyramids

the Kushite Empire was mentioned and its name meaning “bird”

in Turkish was questioned. The reason being that, this word is

found in languages that have been separated for very long

periods of time. This word meaning “bird” is found as

kus in the Sumerian

language and as kutz

in the Maya language (1).

As no words could have been borrowed from Sumerian to Mayan or

vice-versa, the only logical explanation is that Sumerian,

Mayan and Turkish stem from a common root language, which is

the Asiatic Proto-language.

But there is

one more clue supporting the Central Asiatic origin of this

word. This clue is found in the name of an Empire known as the

Kushan Empire,

which lasted from the first to the third centuries AD, but has

a much ancient beginning. The Kushan name is clearly made out

two words Kush and Han meaning “bird” and “king”, where “Han”

is a late version of the “Khan” title used also for Ottoman

emperors.

The bird has

been an important animal for ancient cultures, symbolizing the

solar deity (see Chapter 29,

The bird symbolism). Below we see the territories

controlled by the Kushan Empire. It extended from western

China on the east, to Bactria on the west and included the

Indus Valley as well as most of northern India.

In the

name of the

Hindu-Kush

Mountains (shown on the map) we can still find the connection

between Hind (ancient India) and Kush (the Kushan Empire). The

Kushan Empire included important cultural centers such as Belh

(Bactra), Kashgar, Kucha, Turfan and the capital city

Ghandara. The northern region of the ancient Kushan Empire is

defined nowadays as BMAC (see Chapter 16,

The south-west expansion).

This vast region has been the land of the Saka (As-Okh /

Scythians), the Sarmatians, the Kushans and the Alans.

The people

forming the Kushan Empire were descendents of the Central

Asiatic Yueh-chi or

Yuezhi tribes who

were nomads traveling long distances. They even went up to the

north-eastern regions of Asia for fur trading. There are

numerous theories about the derivation of the name Yuezhi. My

own interpretation is that these Asiatic people defined

themselves as “superior”, a word pronounced as

Yuedje in Turkish.

This meaning is quite possible considering that the difficult

phoneme “dje” -not found in Chinese- has been replaced, most

probably, by the “zhi” sound, which is quite common in

Chinese.

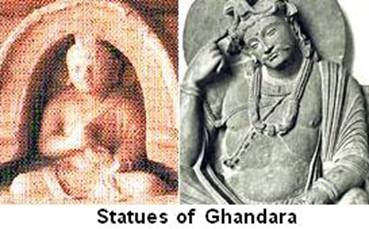

There are

several statues found in Ghandara indicating the dressing

style of the Kushan rulers. In the pictures below we see two

such examples where the right arm has been left uncovered. Luc

Kwanten says the following about this dressing habit

(2):

Uighur representations of Buddhist saints, like the Chinese,

are always clothed, whereas in the Gandhara style, at least

one of the shoulders is naked.

This

dressing style has already been identified among the Sumerian,

the Indus Valley kings and the spiritual leader of present

Tibet (see Chapter 17, The

Indus Valley script).

An important

Kushan ruler is known under the name Mahasena Huvishka (circa

155 to 187 AD). The coin shown below belongs to this king, but

the letters stamped on the coin do not agree with either

Mahasena or Huvishka. I tried to read the stamped name with

the help of the ancient Turkish (Orhun) letters, as shown

below-right.

Except the

two first letters H and a, which also are of Asiatic origin

(3),

the remaining letters on the coin perfectly agree with the

Orhun letters shown in red. The transcription then becomes

“Hakantekin”, where Tekin or Tigin is a Turkish title given to

minor regional kings or princes.

At the Orhun

Valley in Central Asia we have the

Kül Tigin

stele, which is 3.35 m high and contains several lines of

Turkish inscriptions written with the Orhun characters. The

scribe has added his name at the end of the inscriptions as:

Yollugh Tigin

(4).

The coin

above has two more interesting clues which are worth

mentioning. The first one is the bird held in the right hand

of the king, a possible indication to “Kush-Han” (bird-king)

and the next clue is the pelerine wore by the king. We find a

similar pelerine on the young Saka (Scythian) prince (see

Chapter 23, The Issýk kurgan). |